The FBI wants to use artificial intelligence to add a new layer to its Next Generation Identification (NGI) system, specifically to counteract the increasingly common practice of criminals altering their fingerprints.

In a Sources Sought notice issued at the end of August, the FBI said it has seen a “growing trend” among criminals of intentionally altering their fingerprints so that what they leave behind at a crime scene doesn’t ring any bells with the bureau’s NGI system. The FBI is looking for AI-powered technology that can detect not only known methods of altering fingerprints but any newer methods they might come up with. “As those who seek to avoid identification continue to evolve their alteration techniques, it is critical that the NGI System maintain pace through the ability to learn in real time,” the notice said.

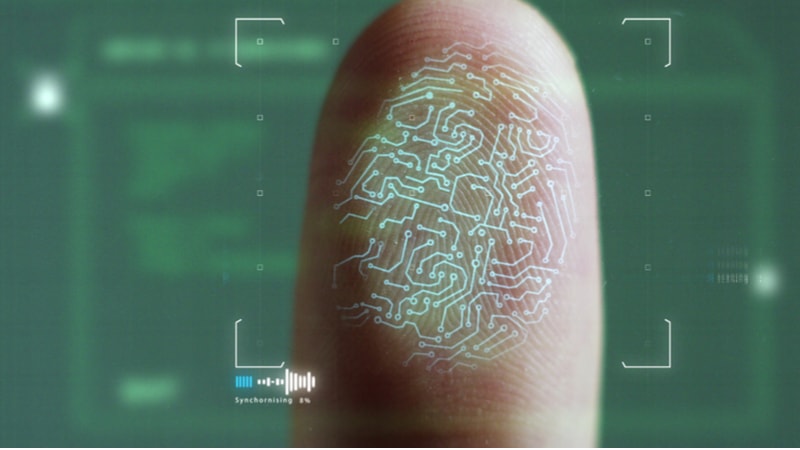

Fingerprints have been used as a unique biometric identifier since the late 19th century. They have been accepted in U.S. courts for more than 100 years as solid proof that someone was at the scene of a crime, held a murder weapon, or otherwise could be held accountable for an illegal action. And while faking fingerprints–particularly for digital purposes–has become more common with new technology, actually changing the ridge patterns on one’s fingers is still done the old-fashioned way, which is to say with difficulty and pain.

The practice is becoming common among those with criminal histories whose fingerprints are already in the FBI’s database, the bureau said in a warning issued a few years ago. Common tricks include several methods of cutting (vertical slices or a Z pattern), burning using acid or another method, abrading, or having surgery performed, to “obliterate, distort, or imitate fingerprints of other individuals,” the FBI said. Fingerprints also can be altered unintentionally over time through work that involves constant contact with chemicals or rough materials such as bricks. Some diseases and medical treatments also can affect the features of a fingerprint.

Regardless of how changes occur, the FBI wants to know when they’ve happened, and is hoping for an AI system that can do the job. AI techniques in machine learning and deep learning have made significant improvements in recent years at performing tasks they were specifically trained to do, but still struggle to learn from examples and take the next steps on their own.

Law enforcement has good reason to seek better ways of analyzing fingerprints, because, aside from physically altering a print, technology has made it pretty easy these days to fake a print. Hackers have found it fairly easy—using, for instance, dental mold—to fake a print to gain access to a smart phone. In 2016, researchers demonstrated how they used an ink jet printer to fake fingerprints of the kind that could be stolen from personnel files—such as those taken in the 2014 hack of the Office of Personnel Management that involved information on 22 million people.

These days, faking fingerprints is becoming something of a hobby. There’s a WikiHow with 13 step-by-step instructions and elementary school-level illustrations on how to do it. A piece in the Christian Science Monitor even promotes faking fingerprints as a way to protect your privacy.

Eventually, the trusty fingerprint might reach the point of being unreliable, which is one reason researchers are working on a range of potentially more accurate biometric alternatives. But in the meantime, the FBI’s NGI system will remain an essential tool in identifying suspects, and machine learning techniques could keep ahead of those who alter or fake their fingerprints.