At the heart of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) new satellite is the Advanced Baseline Imager (ABI), a high-powered digital camera 12 years in the making.

Eric Webster, vice president and general manager of environmental solutions at Harris Corp., said that the ABI is the main instrument aboard the satellite. Harris Corp., an IT equipment company, built the ABI and the ground systems unit for NOAA’s Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite-R (GOES-R), set to launch Nov. 4. NOAA awarded Harris the contract to build the ABI in 2004.

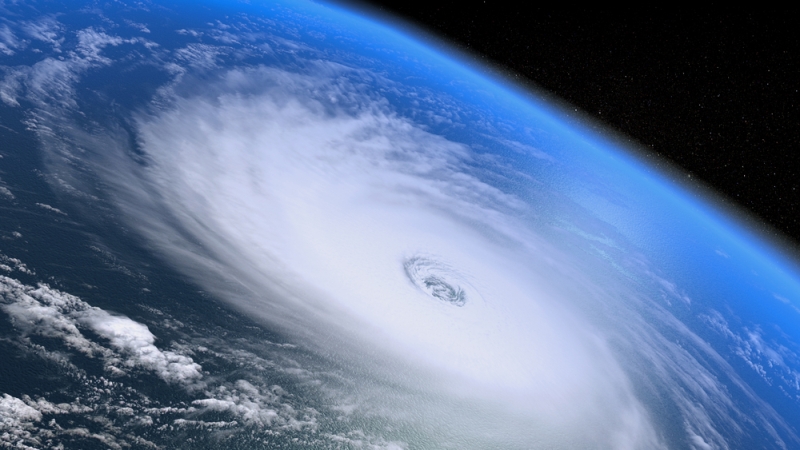

The ABI is a weather satellite that will fly 22,300 miles above Earth, taking pictures of storms and the ocean in order to provide quick and accurate information to forecasters. Webster compared it to the world’s most advanced digital camera, as it can zoom in to certain weather patterns, like a hurricane, while still maintaining an accurate view of the hemisphere and the United States. It can run these full scans in 15 minutes, which is half the time the current weather satellites can perform the same task. Webster said the resulting data created a sort of stop-motion film of developing storms.

“You’re going to get a virtual movie of a hurricane or tornado outbreak,” Webster said.

In addition to speed, the ABI will also provide thermal and infrared filters that will enable scientists to study the amount of water vapor and precipitation in different storms. The GOES-R satellite is the first of four weather satellites that NOAA plans to launch in the coming years. GOES-R will park over the east coast of the United States; GOES-S, scheduled to launch in 2018, will stay over the west coast. A roving spare satellite will hover between the two in case one gets damaged. The ABI, situated aboard the satellite, will last 15 years, a lifetime twice as long as the current satellite’s.

Webster also said that this instrument is more precise than its predecessors, as ABI is capable of measuring sea surface temperature to the tenth of a degree.

“If I put a thermometer in my daughter’s ear, I’m lucky if I can get a reading to the tenth of a degree,” Webster said. “These machines do it from 22,000 miles away.”

After receiving the contract in 2004, Harris spent five years designing and developing the instrument. They constructed a full-size replica of the ABI for NOAA’s approval, and then built all four satellites over a series of four years. Webster said the instrument was put together slowly, with mirrors, telescopes, and radiators added on one by one. He also said the ABI had to be tested by being shaken and placed in a thermal chamber to ensure the machine could withstand the drastic temperature changes in space.

“Think about if your camera had to work in Antarctica on its coldest day and then in Death Valley the next day,” Webster said. “It’s really an art. It’s not a science.”